Caitlin Moran's next minute

I found Caitlin Moran's heartfelt open letter to her teenage fans moving and upsetting to read.

Caitlin Moran is certainly right to point to a very unpleasant aspect of modern life: the hysteria that surrounds young girls. I think her letter is intended to defuse some of that hysteria, but I would love her to write a letter to me, because I think she should target the source of the hysteria not its object.

She's right that there are teenage girls who hate themselves, and harm and sabotage themselves, because they are trying to find ways to cope with their own overwhelming feelings. They cannot see any other outlet than to hurt themselves. And something is fuelling that.

Yes, this self-loathing exists, I can attest to the fact myself – not in my own girl, I hope, but certainly in my own memories.

And I do love Moran's promise to our girls, that we only ever have to face the next minute. This is wonderful advice, and probably shows that Moran has done a Mindfulness course. Because this message about the moment is the message of the moment. I wish someone had told me I only had to face the next moment back in the 1980s.

It seems to me that we are currently clinging to Mindfulness, because we have lost any sense of Stoicism in our public and private culture. We are trying to re-mind ourselves that, by simply existing in the here and now, in this minute, we are fully able to face the entry to the next minute. This message carries immense power – and a whiff of despair. Although the advice has been around for thousands of years, it is currently being liberally sprinkled on everything that moves, as the only seasoning any of us can think of to combat the intense multiplication of stressors in contemporary life.

Again, I can attest to the fact myself, because I, too, have clambered on that bandwagon. I'm forever telling my daughter and son to breathe. Usually when the only person in the situation who needs to do so is me.

I also appreciate Moran doing that other, very fashionable, thing – basing her thinking on current neuroscientific research. In the absence of a soul, we now have flooding hormones and over-active neurotransmitters. She tells girls about the heightened levels of adrenalin and cortisol, which are what are provoking the panic in their brains: 'That panic and anxiety will lie to you – they are gonzo, malign commentators on the events of your life. Their counsel is wrong. You are as high, wired and badly advised by adrenaline as you would be by cocaine.' She's not wrong – but nor is it the only explanation for why girls internalise anxiety. It's coming at them from somewhere.

When finally, Moran alludes darkly to the reasons why so many young girls seem to turn their anxiety in on themselves: 'Things have been done', I want to know more. But she does not go into those reasons, because it is not the purpose of this particular letter to go into what, exactly, has been done.

What has been done is what has been going on for centuries. Girls of twelve to sixteen are the most beautiful they will ever be, but they are not ready for the desire of others, and their own desires. Not ready, simply because it takes a long time to learn about one's own desires, and young girls are constantly being targeted and thrown off course by the leering glances of middle-aged men, and the predations of the beauty industry. They are constantly fed an ambivalent line about doing their best, when what is meant is 'be perfect'. The 'selfie' culture is a manifestation of what it is like to be twelve, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen… any age of transition when one is desperate for a reflection of what one is, anything that will stabilise the madness. A girl of that age is changing more rapidly and absolutely than at any time since she learnt to walk. It is dizzying, and she has to do it all under a lascivious spotlight. It makes me feel ill. When I was 17, it literally made me sick.

At the Bat Mitzvah party my twelve-year-old girl went to last night, I watched in fascination, pride… and terror, as a group of young girls danced like fluttering frangipani blossom under a twirling discoball in a dazzlingly white disco. They were unutterably, unbearably beautiful. They were girl-women, safe and protected from unsavoury gazes, loving themselves, happy and delighting in themselves.

It was I, and the other mothers, the dark duennas ranged along the wall, in our black faux-fur-trimmed winter coats, who gripped our arms tightly across our chests, and bit our bottom lips as we looked on. We want too much for our daughters. We don't know what we want for them. We are potentially, if not actually, the problem. We are the Motherloaders. As it was done to us, so we feel we cannot help but do unto our girls. Pull your skirt down. Be good. You're beautiful. Try harder.

I want someone to help me not to pass my worries for my glorious girl-child onto that glorious girl-child.

But the only person who can do that is me.

Minute by minute. Breathing when it gets too much, and her growingness overwhelms me. Keeping my own feet glued to the earth, to try to steady myself as I watch her teeter away. Aching as she separates from me, goes towards her own life.

Moran says a beautiful thing when she suggests that girls can be their own mothers: 'Pretend you are your own baby. You would never cut that baby, or starve it, or overfeed it until it cried in pain, or tell it it was worthless. Sometimes, girls have to be mothers to themselves. Your body wants to live – that’s all and everything it was born to do. […] Protect it.'

When my daughter read her piece, however, what stood out for her was, 'You were not born scared and self-loathing and overwhelmed'. That's what she holds onto, as her teeming emotions buck her every which way, and she hunches her shoulders, and feels scared to stand tall.

Perhaps it's a stretch too far for a twelve-year-old to imagine herself as her own baby, when she has never had a baby. My open letter to my daughter reads: 'I promise you that I will help you to be able to deal with worry and anxiety. It does not have to harm you'.

Caitlin Moran is certainly right to point to a very unpleasant aspect of modern life: the hysteria that surrounds young girls. I think her letter is intended to defuse some of that hysteria, but I would love her to write a letter to me, because I think she should target the source of the hysteria not its object.

She's right that there are teenage girls who hate themselves, and harm and sabotage themselves, because they are trying to find ways to cope with their own overwhelming feelings. They cannot see any other outlet than to hurt themselves. And something is fuelling that.

Yes, this self-loathing exists, I can attest to the fact myself – not in my own girl, I hope, but certainly in my own memories.

And I do love Moran's promise to our girls, that we only ever have to face the next minute. This is wonderful advice, and probably shows that Moran has done a Mindfulness course. Because this message about the moment is the message of the moment. I wish someone had told me I only had to face the next moment back in the 1980s.

It seems to me that we are currently clinging to Mindfulness, because we have lost any sense of Stoicism in our public and private culture. We are trying to re-mind ourselves that, by simply existing in the here and now, in this minute, we are fully able to face the entry to the next minute. This message carries immense power – and a whiff of despair. Although the advice has been around for thousands of years, it is currently being liberally sprinkled on everything that moves, as the only seasoning any of us can think of to combat the intense multiplication of stressors in contemporary life.

Again, I can attest to the fact myself, because I, too, have clambered on that bandwagon. I'm forever telling my daughter and son to breathe. Usually when the only person in the situation who needs to do so is me.

I also appreciate Moran doing that other, very fashionable, thing – basing her thinking on current neuroscientific research. In the absence of a soul, we now have flooding hormones and over-active neurotransmitters. She tells girls about the heightened levels of adrenalin and cortisol, which are what are provoking the panic in their brains: 'That panic and anxiety will lie to you – they are gonzo, malign commentators on the events of your life. Their counsel is wrong. You are as high, wired and badly advised by adrenaline as you would be by cocaine.' She's not wrong – but nor is it the only explanation for why girls internalise anxiety. It's coming at them from somewhere.

When finally, Moran alludes darkly to the reasons why so many young girls seem to turn their anxiety in on themselves: 'Things have been done', I want to know more. But she does not go into those reasons, because it is not the purpose of this particular letter to go into what, exactly, has been done.

What has been done is what has been going on for centuries. Girls of twelve to sixteen are the most beautiful they will ever be, but they are not ready for the desire of others, and their own desires. Not ready, simply because it takes a long time to learn about one's own desires, and young girls are constantly being targeted and thrown off course by the leering glances of middle-aged men, and the predations of the beauty industry. They are constantly fed an ambivalent line about doing their best, when what is meant is 'be perfect'. The 'selfie' culture is a manifestation of what it is like to be twelve, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen… any age of transition when one is desperate for a reflection of what one is, anything that will stabilise the madness. A girl of that age is changing more rapidly and absolutely than at any time since she learnt to walk. It is dizzying, and she has to do it all under a lascivious spotlight. It makes me feel ill. When I was 17, it literally made me sick.

At the Bat Mitzvah party my twelve-year-old girl went to last night, I watched in fascination, pride… and terror, as a group of young girls danced like fluttering frangipani blossom under a twirling discoball in a dazzlingly white disco. They were unutterably, unbearably beautiful. They were girl-women, safe and protected from unsavoury gazes, loving themselves, happy and delighting in themselves.

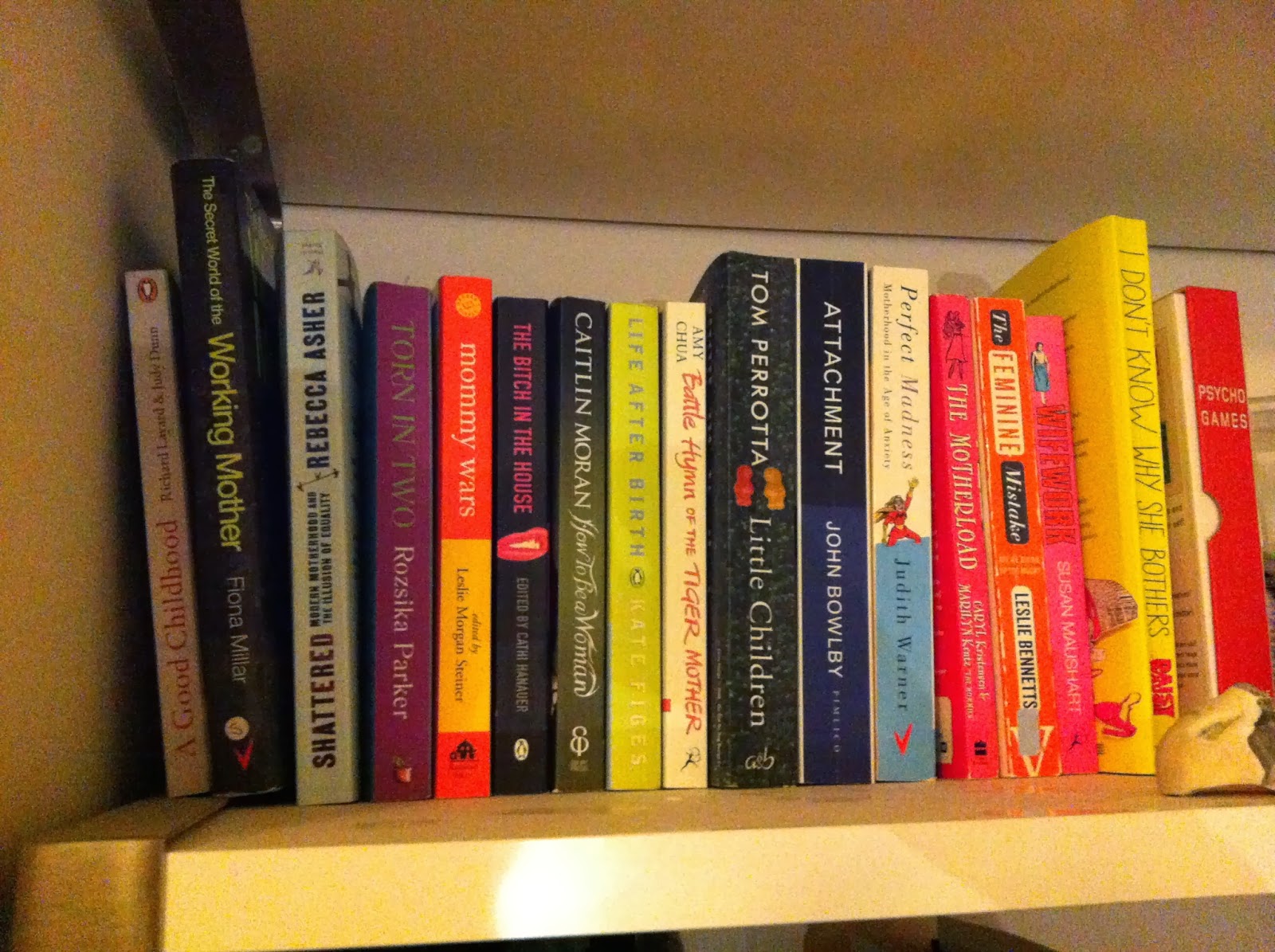

It was I, and the other mothers, the dark duennas ranged along the wall, in our black faux-fur-trimmed winter coats, who gripped our arms tightly across our chests, and bit our bottom lips as we looked on. We want too much for our daughters. We don't know what we want for them. We are potentially, if not actually, the problem. We are the Motherloaders. As it was done to us, so we feel we cannot help but do unto our girls. Pull your skirt down. Be good. You're beautiful. Try harder.

I want someone to help me not to pass my worries for my glorious girl-child onto that glorious girl-child.

But the only person who can do that is me.

Minute by minute. Breathing when it gets too much, and her growingness overwhelms me. Keeping my own feet glued to the earth, to try to steady myself as I watch her teeter away. Aching as she separates from me, goes towards her own life.

Moran says a beautiful thing when she suggests that girls can be their own mothers: 'Pretend you are your own baby. You would never cut that baby, or starve it, or overfeed it until it cried in pain, or tell it it was worthless. Sometimes, girls have to be mothers to themselves. Your body wants to live – that’s all and everything it was born to do. […] Protect it.'

When my daughter read her piece, however, what stood out for her was, 'You were not born scared and self-loathing and overwhelmed'. That's what she holds onto, as her teeming emotions buck her every which way, and she hunches her shoulders, and feels scared to stand tall.

Perhaps it's a stretch too far for a twelve-year-old to imagine herself as her own baby, when she has never had a baby. My open letter to my daughter reads: 'I promise you that I will help you to be able to deal with worry and anxiety. It does not have to harm you'.

Comments